(Scientific American) Most of us could use more sleep. We feel it in our urge for an extra cup of coffee and in a slipping cognitive grasp as a busy day grinds on. And sleep has been strongly tied to our thinking, sharpening it when we get enough and blunting it when we get too little.

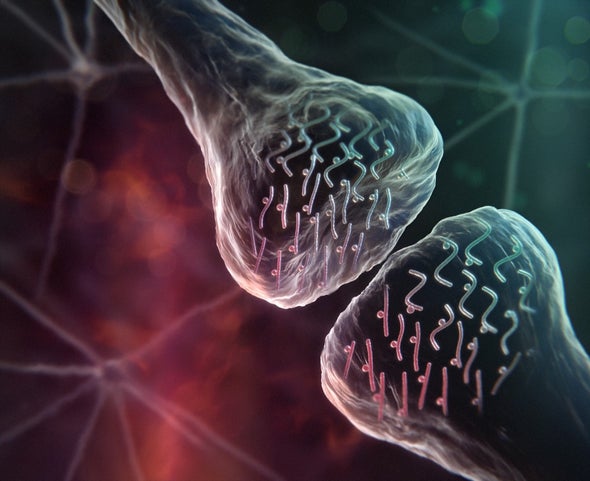

What produces these effects are familiar to neuroscientists: external light and dark signals that help set our daily, or circadian, rhythms, “clock” genes that act as internal timekeepers, and neurons that signal to one another through connections called synapses. But how these factors interact to freshen a brain once we do sleep has remained enigmatic.